In the wake of President Trump’s early April executive order seeking to curtail states’ ability to legislate on climate pollution, which singled out California’s cap and trade program as “fundamentally irreconcilable with my administration’s objective to unleash American energy,” California Governor Gavin Newsom and Democratic state legislators announced plans on Wednesday to reauthorize the program later this year.

California’s Republican Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger proposed and signed cap and trade into existence in 2006, and Democratic Governor Jerry Brown reauthorized it in 2017. According to the state’s Air Resources Board, California has funded $28 billion in climate investments and created 30,000 jobs in the past decade through the program, which sets a declining annual total emissions cap and requires polluters to buy allowances or offsets, and is set to expire in 2030. “California’s efforts to cut harmful pollution won’t be derailed by a glorified press release masquerading as an executive order,” Newsom said in a statement.

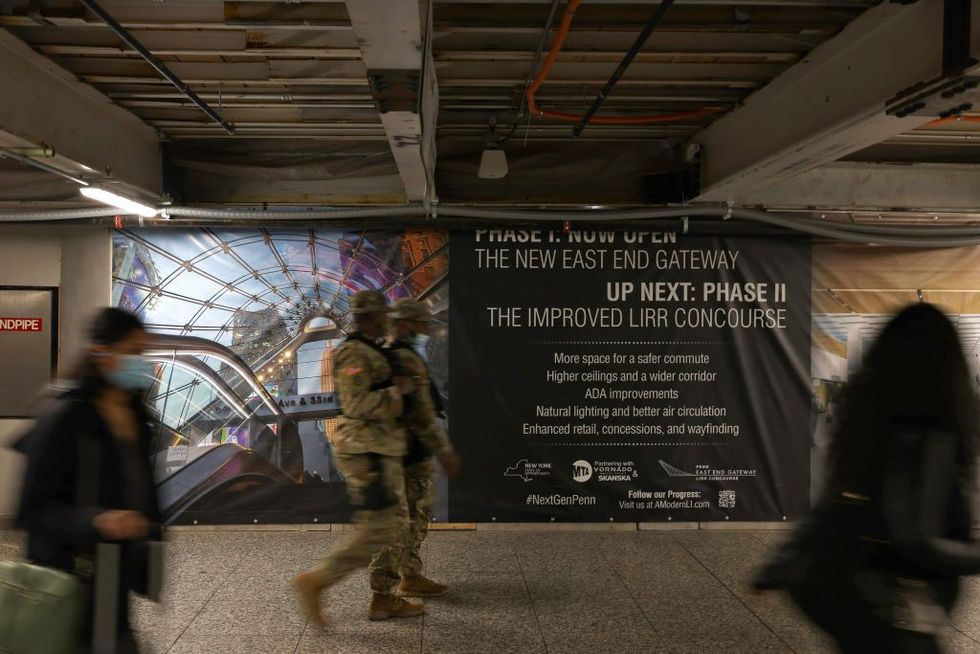

2. Trump administration announces intent to take down New York’s Empire Wind

The Trump administration announced Wednesday its intent to “immediately halt all construction activities on the Empire Wind Project until further review of information that suggests the Biden administration rushed through its approval without sufficient analysis,” Heatmap’s Emily Pontecorvo and Jael Holzman report. If indeed halted, the project would mark the first time the Trump administration has stopped an offshore wind project under construction. As Emily and Jael note, canceling Empire Wind would be disastrous for New York State’s climate goals, since offshore wind was supposed to be a path forward from the New York City area’s current reliance on natural gas, which had replaced carbon-free energy after the Indian Point nuclear plant closed in 2021. In a statement, the American Clean Power Association, the country’s largest renewables trade association, slammed the administration’s decision and argued that “halting construction of fully permitted energy projects is the literal opposite of an energy abundance agenda.”

And in case you missed it, Emily also scooped on Wednesday that Occidental Petroleum has bought direct air capture startup Holocene for an undisclosed amount.

3. Subaru debuts new EV aimed at the Rivian crowd

In a surprise debut at the New York Auto Show, Subaru unveiled its newest electric vehicle: the Trailseeker, a crossover thatInside EVs described as “a step up from the Solterra in just about every way.” The Trailseeker is notably aimed at the “outdoorsy lifestyle” crowd and could compete with the upcoming Rivian R2, both of which are expected to enter production in 2026, TechCrunch writes. The Trailseeker will also be Subaru’s fastest vehicle in the U.S., with 375 horsepower that can kick it from 0 to 60 miles per hour in 4.3 seconds and more cargo space than the Solterra, the automaker’s other EV. But range “isn’t the Trailseeker’s strong point,” Engadget notes, with a charge topping out at 260 miles, and “charging won’t be blazingly fast either as it’s limited to 150 kilowatts.” While it doesn’t have a price tag yet, Jalopnik expects a starting price in the ballpark of $45,000.

Subaru

Subaru

4. Crux raises $50 million Series B funding

Crux, a New York-based capital markets platform that helps facilitate the transfer of tax credits under the Inflation Reduction Act to clean energy and manufacturing projects, announced Wednesday that it had closed a $50 million Series B funding round. Lowercarbon Capital, which also led Crux’s seed round, led the latest round of funding, which featured several new investors. Crux said it intends to use the funding to expand its network, diversify its transaction types, advance its software platform, enhance its market pricing tool Cruxtimate, and scale its team.

“We’re in a new era of global competition, with energy demand rising to the highest levels ever observed,” Alfred Johnson, the CEO and co-founder of Crux, said in a statement. “This new round of funding will help us to meet growing energy demand by making it easier, faster, and more affordable for clean energy developers and manufacturers to finance their projects.”

5. Entirety of Puerto Rico loses power in island-wide blackout

All of Puerto Rico was without electricity on Wednesday after every power plant on the island went out of service at once. According to the director of Luma Energy, which distributes power to the territory, complete restoration to its 1.4 million clients could take up to 72 hours. The exact cause of the blackout is not yet known.

Since Hurricane Maria in 2017, blackouts have not been uncommon on the island — hospitals and the many hotels hosting Easter-week tourists are operating on generators, The Associated Press reports. Puerto Rico’s energy czar, Josué Colón, previously warned of likely summer power problems due to an anticipated lack of generating capacity to meet peak demand. “They have to improve,” one local told the AP. “Those who are affected are us, the poor.”

THE KICKER

Researchers have found “the strongest indication yet of extraterrestrial life” on a planet 120 light-years from Earth, The New York Times reports. The planet’s atmosphere contains a “tremendous supply” of dimethyl sulfide, which on Earth has only one known source: living marine organisms, such as algae.

Michael M. Santiago/Getty Images

Michael M. Santiago/Getty Images

Subaru

Subaru