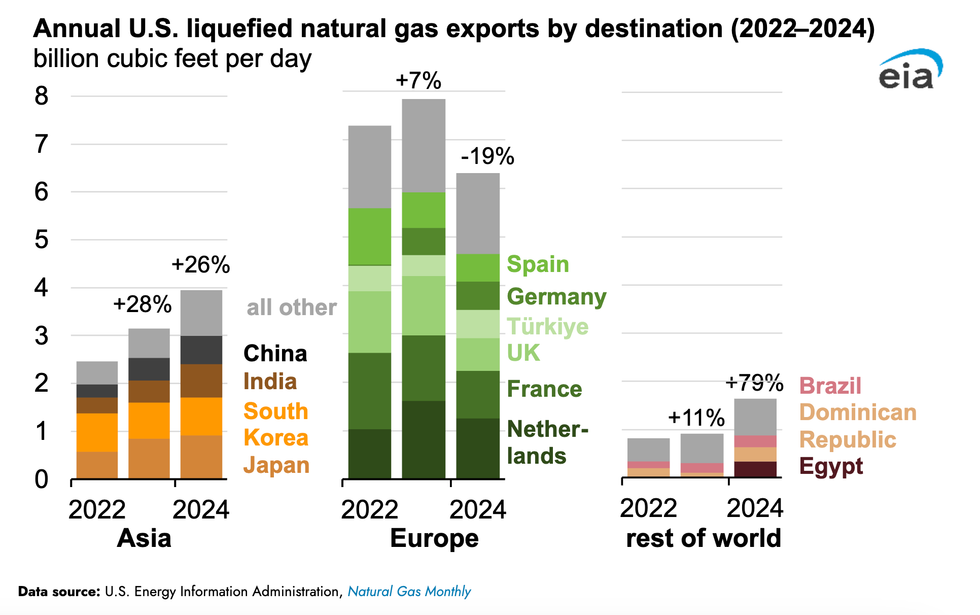

As my colleague Emily Pontecorvo has written, China had been a “relatively small buyer” of U.S. LNG, with only about 5% of American exports heading to the country last year. That number had been “set to rise rapidly over the next few years, however, as Chinese companies have signed a number of long-term contracts with U.S. LNG projects that are about to come online.” China, meanwhile, has turned to Russia — which has been selling gas for cheap since Europe’s boycott following the invasion of Ukraine — to meet its needs.

Nearly half of the U.S.’s LNG exports went to Europe last year, but some analysts on the continent have also begun to warn against relying on American gas due to Trump’s disregard for U.S.-EU trade norms. “We are going from one problematic dependency — on Russian pipeline gas — to another, on U.S. LNG,” Arne Lohmann Rasmussen, chief analyst and head of research at Denmark’s Global Risk Management, told Gas Outlook.

U.S. Energy Information Administration

U.S. Energy Information Administration

2. Pope Francis, who urged protection of the environment, dies at 88

Pope Francis, who raised awareness of climate change and called for it to be addressed with “swift and unified global action,” died on Monday, the Vatican announced. Francis had been in poor health, having been hospitalized for five weeks earlier this year, but he managed to appear for crowds on Easter Sunday for the traditional blessing from the balcony of St. Peter’s Basilica.

Central to Francis’ legacy are his consistent and urgent calls to protect the environment. In 2015, he published his 184-page Laudato si’: On Care for Our Common Home, in which he described climate change as “a global problem with grave implications: environmental, social, economic, political, and for the distribution of goods,” and “one of the principal challenges facing humanity in our day.” In 2019 he called “ecocide” a sin and a crime against peace, and in 2023 he published a 15-page rebuke of the continued “resistance and confusion” over addressing the climate crisis, writing, “Despite all attempts to deny, conceal, gloss over, or relativize the issue, the signs of climate change are here and increasingly evident.” Poor health prevented Pope Francis from attending COP28 in Dubai that year to deliver a companion speech, but in 2024, the Vatican arranged a three-day conference on the climate, at which the pope warned political leaders to examine whether “we are working for a culture of life or for a culture of death.”

3. OPM officially files paperwork to reinstate Schedule F

On Friday, the Office of Personnel Management filed proposed regulations to bring back Schedule F, which would reclassify and strip civil service protections from an estimated 50,000 federal workers. Now renamed “Schedule Policy/Career,” the proposal has been tweaked from the original Schedule F plan that Trump implemented at the end of his first term “to make it more legally palatable, including moving the final decision-making authority regarding the conversion of jobs to the president, rather than the OPM director,” Government Executive writes.

As I’ve written before, the Trump administration designed its reclassification of federal employees to “make it easier to replace ‘rogue’ or ‘woke’ civil servants and would-be whistleblowers, a.k.a. ‘the deep state,’ with party-line faithful.” Daniel Farber, the director of the Center for Law, Energy, and the Environment at the University of California, Berkeley, warned me that “What we’re going to end up with is an executive branch that’s just uninformed.”

4. Trump administration cuts health program focused on protecting first responders from EV fires

The Department of Health and Human Services has eliminated the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s firefighter health program, including research by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health into how to protect first responders from the dangers of electric vehicle fires, E&E News reports. The cuts were part of an 18% reduction in the HHS workforce and the nearly complete elimination of NIOSH in the name of government efficiency. The research was critical, advocates say, because EV batteries release harmful chemicals and toxins when they burn, necessitating different safety measures than those for other types of fires.

“In firefighting, it’s always, ‘Guess what, this is bad,’ after you’ve been exposed to it for 40 years,” Tim Ferretti, a CDC researcher who was recently laid off, told E&E News, adding, “But with electric cars, NIOSH was trying to be ahead of the game and stop a potential problem before it becomes a chronic issue.”

5. Chinese scientists make breakthrough with world’s first operational thorium molten salt reactor

Chinese media reported on Friday that the country has successfully reloaded fuel into a working thorium molten salt reactor, making it the world’s first stable, operable reactor of its type. The experimental unit, located in the Gobi Desert of Mongolia, reportedly generates 2 megawatts of thermal power, according to Interesting Engineering.

MSRs use molten salt as a fuel carrier and coolant (instead of water) and thorium — an abundant radioactive element — as their fuel source. Many consider MSRs to be a safer form of nuclear power because they don’t use uranium, which can be “weaponized,” and they have far less risk of a meltdown because “salts can carry greater loads of thermal energy at much lower pressure” than water, Futurism writes. Due to the technical hurdles of creating an operable MSR, research by U.S. scientists tapered off after the 1940s and 1950s, was “assumed obsolete,” and had been made publicly available — reportedly serving as the backbone of the breakthrough by China. As the project’s chief scientist Xu Hongjie said in his closed-door announcement of the MSR’s success to the Chinese Academy of Sciences, “Rabbits sometimes make mistakes or grow lazy. That’s when the tortoise seizes its chance.”

THE KICKER

“The cameras are staying on.” —A spokesperson for New York’s Democratic Governor Kathy Hochul on the state’s decision to continue charging cars a toll for entering Lower Manhattan past Sunday, the Trump administration’s deadline for ending congestion pricing.

Image: David Ryder/Getty Images

Image: David Ryder/Getty Images

U.S. Energy Information Administration

U.S. Energy Information Administration