Technology

The Search for a Somewhat Sustainable Aviation Fuel

Money is pouring in — and deadlines are approaching fast.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

Money is pouring in — and deadlines are approaching fast.

Trump’s first administration supported it. But now there’s a new crowd coming into town.

Embarrassed to be driving a Tesla these days? You’re not alone.

On water stress, private jets, and the campaign’s home stretch.

Berkeley-based Copper was selected to supply 10,000 stoves to the New York City Housing Authority.

To do it right, you’re going to need a building science pro.

When Zara Bode, a musician from Brooklyn, New York, first walked into the old seven-bedroom Victorian in downtown Brattleboro, Vermont, it just felt right. Her husband, also a traveling musician, had grown up nearby. “You walk in this house and you’re like, oh, there’s a good vibe,” she told me. Since the 1890s, when it was built, it had been a community health center and a food co-op, before being lovingly restored by the older woman who sold it to Bode and her husband in January of 2020. Bode hoped to make it their forever home, a place for friends and family to gather.

Within a month of moving in, she and her husband both lost their incomes in the pandemic. Then they made a brutal discovery: the house was ruinously expensive to heat.

They spent all their time huddled in the kitchen with their two young children in front of the wood burning cookstove and kept the thermostat at 65. Even so, they were running through a full tank of oil every nine days. Each delivery cost more than $1,000, adding up to twice their mortgage every month. They had to ask for government emergency assistance.

Bode started asking around to other families, who told her about a state-funded program that gives out 0% weatherization loans with deferred repayment to low-income families. She got quotes from two different reputable companies, each of which proposed using polyurethane spray foam insulation in the large basement. The buzz in the community was that spray foam is a miracle product — so incredibly insulating that it would cut their heating oil needs down by two-thirds or or more. But Bode was protective of the old Victorian. “I knew it was lucky for us to get this house in the first place. We don’t have the money to make mistakes,” she says.

Without any outside expert to turn to, desperate for relief, and grateful for Vermont’s robust social safety net, she went for it.

She would come to regret it.

To hit its climate goals, the U.S. is going to have to upgrade its old housing stock. Residential energy use accounts for about 20% of U.S. carbon emissions, and the lion’s share of that energy is used to heat and cool homes. At the same time, low-income families are struggling more than ever to shoulder the financial burden of doing that. In 2023, the number of American families needing assistance jumped by 1.3 million to over 6 million.

The Inflation Reduction Act is aiming to tackle these twin crises, with a tax credit covering 30% of the cost of insulation and air-sealing materials, up to $1,200 annually per household. So far only New York has an active IRA-funded home rebate program, but more states have applied to start handing out funds to homeowners over the next year, which should also help shield Americans from the health effects of extreme temperatures.

The problem is, insulating an old home is a delicate and complex process. Improper installation can lead to mold, dry rot in your home’s framing and roof, and poor indoor air quality that can make you sick.

“It’s potentially a huge problem,” Francis Offerman, a.k.a. Bud, an industrial hygienist who does indoor air quality testing for homeowners (and lawyers) who suspect a house or apartment is making its inhabitants ill, told me. “Especially if your mindset is, we’re going to just spray foam the home, and that’s it.”

Bode reached out to me last year after she read my viral story for VT Digger, which raised the alarm about the risks of spray foam insulation in particular. (Though experts say any insulation done badly can cause problems.) She and her family had vacated their Victorian for a few days in early 2021 while the basement was spray foam insulated. When they moved back in, Bode was struck by the bad paint smell. That eventually went away, and oil deliveries dropped from every nine days to every three weeks.

But then she realized the basement, which used to be bone dry, was now damp all the time. She bought two industrial dehumidifiers that run constantly, and still the smell of mildew wafts up through the floorboards. Bode has allergies to mold and mildew and worries the bad air quality could affect her kids, who also have allergies and asthma. She’s had to move all her furniture and art out of the basement lest it get damaged.

When she saw my article, she felt a mix of emotions. On the one hand, after having her concerns dismissed by the insulation company, she finally felt validated. “That was the first time that I had heard about air exchangers and other things I can’t afford,” Bode told me about reading my article. But she wondered, “Did I ruin a house that’s been standing strong for 140 years?”

The kind of person that could have advised Bode on how to safely insulate her historic home would be someone trained in building science — that is, someone educated in the physics of buildings, who can identify moisture issues and air leaks, recommend appropriate materials and HVAC solutions, and give you a step-by-step plan for implementing them so your home stays healthy and whole.

Unfortunately, many insulation companies, architects, and contractors have either never heard of or are actively hostile to these concepts, which they see as expensive, unnecessary, overly complicated, and (in the case of many spray foam contractors) an impediment to making the sale.

“In the grand scheme of things, building science is a relatively new field,” Eric Werling, who recently retired after 30 years of directing the U.S. Department of Energy’s Building America program to run his own consulting business, told me. “People have studied structural engineering for thousands of years. But air-tightening buildings is a relatively new phenomenon.”

Up until the 1970s, people in the U.S. didn’t think much about insulation. Then the energy crisis struck, and oil shortages caused prices to skyrocket. President Jimmy Carter told Americans to put on a sweater and turn down the thermostat. Letting all that expensive energy flow outside suddenly seemed like a waste of money.

The Department of Energy launched its Weatherization Assistance Program in 1976 for low-income families and created efficiency standards for commercial buildings that relied on the new, synthetic materials that had emerged after WWII. The problem was, as homes and commercial buildings were sealed, a lot of people got sick. The most high profile cases were cancer from chronic radon exposure or quiet but shocking deaths from carbon monoxide poisoning. But there also emerged the autoimmune-adjacent condition called Sick Building Syndrome, a constellation of symptoms related to breathing in VOCs from furniture, carpeting, pesticides, and cleaning products circulating inside a tight building.

“The Department of Energy… screwed it up a lot at the very beginning,” Joe Lstiburek, a longtime building science consultant, told me. But the DOE started training its weatherization crews, establishing standards for proper insulation, and providing additional funding for safety measures, including mechanical ventilation. “America became a world leader at figuring out how not to rot houses and how not to kill people,” Lstiburek said.

Today, indoor air quality in the workplace has dramatically improved. Aspects of building science have been codified in residential homes as well, with some states requiring that new builds with a tight air seal include mechanical ventilation. But nobody I talked to could point to similar requirements for an existing home that has been retrofitted with insulation. And when I asked Lstiburek if low-income renters and homeowners have access to building science information and advice, he said, “No, they do not.”

According to Werling, there are still probably fewer than a thousand building science experts, and many are eyeing retirement. “Their teachings have impacted thousands –– probably hundreds of thousands –– of people in the construction industry.” He points to New York and Wisconsin as two states that have had robust contractor training programs for the longest. But he admits that’s still a small percentage of the millions of people involved in construction in the U.S.

“There are just too many companies with people who don’t know enough about the issues regarding moisture doing whatever they want and leaving the homeowner with the bill,” Chris West, a Vermont-based certified consultant and trainer for Passive House, a design standard for ultra-low-energy-consumption homes, told me. “Often these companies have some kind of caveat in their contract that makes the owner responsible for any future issues.”

To make things worse, our homes are more delicate today. New building construction has largely switched from rot- and mold-resistant materials such as hardwood and plaster to cheaper manufactured mold-prone materials like plywood and drywall.

“Green” or “eco” home programs that advise homeowners focus solely on energy efficiency, and tightened energy codes are requiring ever more robust insulation without taking into account existing moisture problems (such as a wet basement or unventilated bathroom), which are not rare. NIOSH estimates about half of all homes have some sort of moisture or mold issue. Residential contractors, architects, and developers, meanwhile, are largely free to ignore building science concepts and go about their business doing things the way they’ve always been done. And there doesn’t seem to be a good plan in place to upskill contractors for this next weatherization push or protect consumers from shoddy workmanship.

“There isn’t an educational track that’s indoor air quality in universities or colleges,” Offerman told me. “I’m 71 now. I’m gonna retire eventually, and where are the replacements?”

I’ve talked to several homeowners who have been burned by bad insulation jobs, and every one expressed dismay that contractors aren’t required to at least share the potential risks or downsides of getting your home weatherized. For example, homeowners may have to install mechanical ventilation at an extra cost of a few thousand dollars, and spray foam, as opposed to traditional batting insulation, is permanent and all but impossible to remediate or take out.

This information is largely hidden from consumers, even savvy ones like me. I was pitched spray foam by an energy auditor for my own old farmhouse, and I had to go out and interview a half dozen experts for an article and pay $1,000 to West to drive two hours down to audit our house (again) and come up with an alternative plan I was comfortable with.

Werling doesn’t want homeowners to be scared away from weatherizing their homes. “In the vast majority of cases, homeowners are better off when they insulate and air-seal their homes,” he said, “but it’s important to be aware that the house is a complicated system of parts. Hire the right contractor to help avoid potentially costly problems down the road.” He points to the Home Improvement Expert section of the Building America Solution Center from the U.S. Department of Energy, which has detailed checklists you can go over with your contractor to ensure the work is done properly. West suggests homeowners find a certified consultant at Passive House Institute US.

The building science experts I spoke to suggested things like an educational program for consumers so they know to ask about ventilation, third party inspections before and after weatherization projects with the results entered into the public record, pre-sale energy audits, and mandatory building science training for contractors and their crews. Offerman said weatherization programs should hold installers accountable for insulating and ventilating according to the latest building science standards as a condition of receiving funds.

The question is how many homeowners like Zara will have their homes and health damaged before the situation is addressed. “It’s not that we don’t know that this is happening,” Listiburek says. “It’s that it’s not painful enough yet.”

It’s flawed, but not worthless. Here’s how you should think about it.

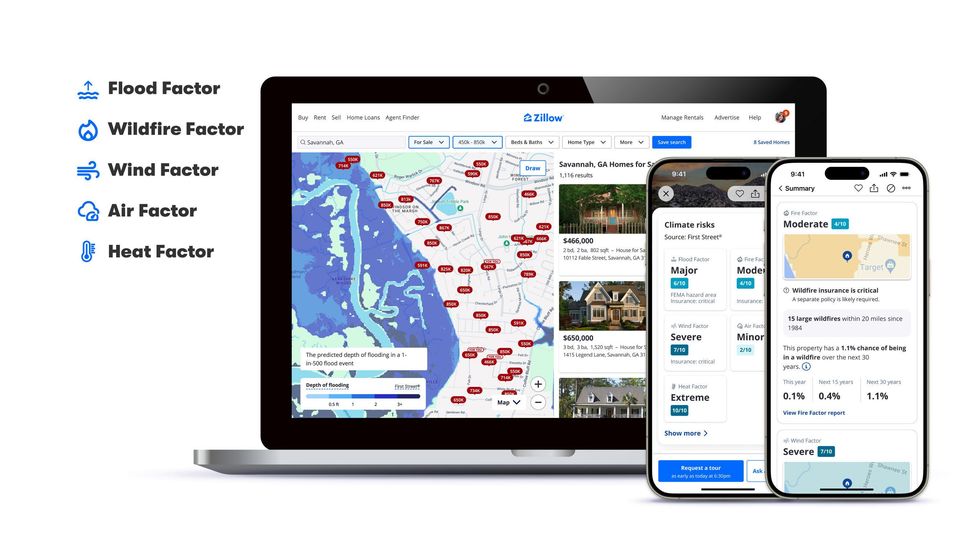

Starting this month, the tens of millions of Americans who browse the real-estate listings website Zillow will encounter a new type of information.

In addition to disclosing a home’s square footage, school district, and walkability score, Zillow will begin to tell users about its climate risk — the chance that a major weather or climate event will strike in the next 30 years. It will focus on the risk from five types of dangers: floods, wildfires, high winds, heat, and air quality.

The data has the potential to transform how Americans think about buying a home, especially because climate change will likely worsen many of those dangers. About 70% of Americans look at Zillow at some point during the process of buying a home, according to the company.

“Climate risks are now a critical factor in home-buying decisions,” Skylar Olsen, Zillow’s chief economist, said in a statement. “Healthy markets are ones where buyers and sellers have access to all relevant data for their decisions.”

That’s true — if the information is accurate. But can homebuyers actually trust Zillow’s climate risk data? When climate experts have looked closely at the underlying data Zillow uses to assess climate risk, they have walked away unconvinced.

Zillow’s climate risk data comes from First Street Technology, a New York-based company that uses computer models to estimate the risk that weather and climate change pose to homes and buildings. It is far and away the most prominent company focused on modeling the physical risks of climate change. (Although it was initially established as a nonprofit foundation, First Street reorganized as a for-profit company and accepted $46 million in investment earlier this year.)

But few experts believe that tools like First Street’s are capable of actually modeling the dangers of climate change at a property-by-property level. A report from a team of White House scientific advisors concluded last year that these models are of “questionable quality,” and a Bloomberg investigation found that different climate risk models could return wildly different catastrophe estimates for the same property.

Not all of First Street’s data is seen as equally suspect. Its estimates of heat and air pollution risk have generally attracted less criticism from experts. But its estimates of flooding and wildfire risk — which are the most catastrophic events for homeowners — are generally thought to be inadequate at best.

So while Zillow will soon tell you with seeming precision that a certain home has a 1.1% chance of facing a wildfire in the next 30 years, potential homebuyers should take that kind of estimate with “a lot of grains of salt,” Michael Wara, a senior research scholar at the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment, told me.

Here’s a short guide for how to think through Zillow’s estimates of climate risk.

Neither First Street nor Zillow immediately responded to requests for comment.

Zillow has said that, when the data is available, it will tell users whether a given home has flooded or burned in a wildfire recently. (It will also say whether a home is near a source of air pollution.)

Homebuyers should take that information seriously, Madison Condon, a Boston University School of Law professor who studies climate change and financial markets, told me.

“If the house flooded in the recent past, then that should be a major red flag to you,” she said. Houses that have flooded recently are very likely to flood again, she said. Only 10 states require a home seller to disclose a flood to a potential buyer.

First Street claims that its physics-based models can identify the risk that any individual property will flood. But the ability to determine whether a given house will flood depends on having an intricate knowledge of local infrastructure, including stormwater drains and what exists on other properties, and that data does not seem to exist in anyone’s model at the moment, Condon said.

When Bloombergcompared the output of three different flooding models, including First Street’s, they agreed on results for only 5% of properties.

If you’re worried about a home’s flood risk, then contact the local government and see if you can look at a flood map or even talk to a flood manager, Condon said. Many towns and cities keep flood maps in their records or on their website that are more granular than what First Street is capable of, she said.

“The local flood manager who has walked the property will almost always have a better grasp of flood risk than the big, top-down national model,” she said.

In some cases, Zillow will recommend that a home buyer purchase federal flood insurance. That’s generally not a bad idea, Condon said, even if Zillow reaches that conclusion using national model data that has errors or mistakes.

“It simply is true that way more people should be buying flood insurance than generally think they should,” she said. “So a general overcorrection on that would be good.”

If you’re looking at buying a home in a wildfire-prone area, especially in the American West, then you should generally assume that Zillow is underestimating its wildfire risk, Wara, the Stanford researcher, told me.

That’s because computer models that estimate wildfire risk are in a fairly early stage of development and improving rapidly. Even the best academic simulations lack the kind of granular, structure-level data that would allow them to predict a property’s forward-looking wildfire risk.

That is actually a bigger problem for homebuyers than for insurance companies, he said. A home insurance company gets to decide whether to insure a property every year. If it looks at new science and concludes that a given town or structure is too risky, then it can raise its premiums or even simply decline to cover a property at all. (State Farm stopped selling home insurance policies in California last year, partly because of wildfire risk.)

But when homeowners buy a house, their lives and their wealth get locked into that property for 30 years. “Maybe your kids are going to the school district,” he said. It’s much harder to sell a home when you can’t get it covered. “You have an illiquid asset, and it’s a lot harder to move.”

That means First Street’s wildfire risk data should be taken as “absolute minimum estimate,” Wara said. In a wildfire-prone area, “the real risk is most likely much higher” than its models say.

Over the past several years, runaway wildland fires have killed dozens of people or destroyed tens of thousands of homes in Lahaina, Hawaii; Paradise, California; and Marshall, Colorado.

But in those cases, once the fire began incinerating homes, it ceased to be a wildland fire and became a structure-to-structure fire. The fire began to leap from house to house like a book of matches, condemning entire neighborhoods to burn within minutes.

Modern computer models do an especially poor job of simulating that transition — the moment when a wildland fire becomes an urban conflagration, Wara said. Although it only happens in perhaps 0.5% of the most intense fires, those fires are responsible for destroying the most homes.

But “how that happens and how to prevent that is not well understood yet,” he said. “And if they’re not well understood yet from a scientific perspective, that means it’s not in the [First Street] model.”

Nor do the best university wildfire models have good data on every individual property’s structural-level details — such as what material its walls or roof are made of — that would make it susceptible to fire.

When assessing whether your home faces wildfire risk, its structure is very important. But “you have to know what your neighbor’s houses look like, too, within about a 250-yard radius. So that’s your whole neighborhood,” Wara said. “I don’t think anyone has that data.”

A similar principle goes for thinking about flood risk, Condon said. Your home might not flood, she said, but it also matters whether the roads to your house are still driveable or whether the power lines fail. “It’s not particularly useful to have a flood-resilient home if your whole neighborhood gets washed out,” she said.

Experts agree that the most important interventions to discourage wildfire — or, for that matter, floods — have to happen at the community level. Although few communities are doing prescribed burns or fuel reduction programs right now, some are, Wara said.

But because nobody is collecting data about those programs, national risk models like First Street’s would not factor those programs into an area’s wildfire risk, he said. (In the rare case that a government isclearing fuel or doing a prescribed burn around a town, wildfire risk there might actually be lower than Zillow says, Wara added.)

Going forward, figuring out a property’s climate risk — much like pushing for community-level resilience investment — shouldn’t be left up to individuals, Condon said.

The state of California is investing in a public wildfire catastrophe model so that it can figure out which homes and towns face the highest risk. She said that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the federal entities that buy home mortgages, could invest in their own internal climate-risk assessments to build the public’s capacity to understand climate risk.

“I would advocate for this not to be an every-man-for-himself, every-consumer-has-to-make-a-decision situation,” Condon said.